Prehistory and History of the Canary Islands

- Carlos Vermeersch

- Mar 23, 2018

- 37 min read

Updated: Apr 20, 2024

The Canary Islands are an enchanting archipelago of seven islands and six islets, which form the bioregion of Macaronesia alongside the Azores, Madeira, Savage Islands and Cape Verde, and are the largest archipelago of this region. Unlike the other islands of Macaronesia, the Canaries have been inhabited since Classical Antiquity, when they were known as the semi-legendary Insulae Fortunatae in Latin and Μακάρων Νῆσοι (Makárōn Nêsoi) in Greek—i.e. the Fortunate Isles or the Isles of the Blest—variously treated as a simple geographical location and as a winterless earthly paradise inhabited by the heroes of Greek mythology.

It was said the Pillars of Hercules bore the warning Non plus ultra («no further») or Non terrae plus ultra («No lands further beyond»), serving as a warning to sailors and navigators, urging them not to venture further. Immersed in Greco-Roman mythology, the Fortunate Isles were known as part of Hades, beyond the Pillars and the boundaries of human settlements known to Greeks as οἰκουμένη (oikouménē, «inhabited [land]»). Legend has it the islands were reserved for those who had chosen to be reincarnated three times, and their souls deemed as exceptionally pure to gain entrance to the Elysian Fields on each occasion.

Note: The following article is a highly summarized version of the original. For more comprehensive articles and quotations from ancient sources in their original language (such as Ancient Greek, Latin, Medieval Arabic, Early Modern Castilian) accompanied by novel and unprecedented transcriptions and translations with commentaries, please visit the main articles corresponding to each section. You can find links to these articles below the heading of each respective section.

Table of contents

Antiquity

Identification of the islands mentioned by ancient authors

Roman presence on the islands

Early and High Middle Ages

Saint Brendan's legendary journey to the Promised Land for Saints

Possible Muslim expeditions

Berber kingdoms prior to the Castilian conquest

Gran Canaria

Tenerife

La Palma

Pre-conquest exploration

Genoese contact

Cerda lordship of Fortuna

Majorcan-Aragonese contact

Portuguese contact

Castilian contact

Legends

Castilian conquest of the Canary Islands (1402–1496)

Aristocratic conquest or conquista señorial (1402–1476)

Norman aristocratic conquest or conquista señorial betancuriana o normanda

Castilian aristocratic conquest o conquista señorial castellana

Royal conquest or conquita realenga(1478–1496)

Conquest of Gran Canaria (1478–1483)

Conquest of La Palma (1492–1493)

Conquest of Tenerife (1494–1496)

Role in the conquest of America

History

Antiquity

The Canary Islands may have been visited by Carthaginian ships. In 435 BC, Carthaginians, led by Hanno the Navigator, embarked on a voyage. They sailed through the Pillars of Hercules at the Strait of Gibraltar and explored the western coast of Africa. The expedition established cities and reached as far south as southern Morocco, and possibly even Senegal or Gabon. The narrative mentions a tall fiery mountain, which some identify as Mount Cameroon or the Teide volcano. The crew encountered a burning country emitting fragrant scents and witnessed torrents of fire flowing into the sea. The extreme heat prevented them from landing, and they sailed swiftly, filled with fear. After four days, they saw the land covered in flames at night, with one particularly tall fire that seemed to touch the stars. This towering fire was referred to as the "Chariot of the Gods." They continued sailing alongside the fiery torrents for three more days until they reached a bay called the Horn of the South.

Arrian, in his work Indica, mentions Hanno's voyage and includes a reference to a volcano. Hanno, a Libyan explorer, departed from Carthage and sailed beyond the Pillars of Heracles (Strait of Gibraltar) into the Outer Sea. He continued eastward for thirty-five days before turning south. However, he encountered various challenges, including a scarcity of water, scorching heat, and streams of lava flowing into the sea. Arrian's account highlights the difficulties faced by Hanno during his voyage.

Pliny the Elder, in his work Historia Naturalis, quotes Statius Sebosus (f. ca. 100 BCE) regarding the Fortunate Islands (Isles of Bliss) and their location. According to Statius Sebosus, there are only two islands that make up the Fortunate Islands: Invallis and Planasia. Invallis is believed to correspond to Tenerife, while Planasia is likely Gran Canaria. These two islands were considered the Fortunate Islands because the eastern islands were arid, and the three westernmost islands were still undiscovered at the time.

Statius Sebosus provides distances between these islands. He states that Junonia, located 750 miles away from Gades (Cádiz), is one of the Fortunate Islands. To the west of Junonia, at the same distance, are Pluvialia and Capraria. Pluvialia only has access to rainwater as a freshwater source. Additionally, at a distance of 250 miles from these islands, opposite the left side of Mauritania and aligned with the eighth hour of the sun's direction, lie the Fortunate Islands. Invallis, one of the islands, is characterized by its undulating surface, while Planasia is named for its distinctive appearance. According to Sebosus, Invallis has a circumference of 300 miles, and trees on the island can grow as tall as 114 feet.

However, the discovery of the Canary Islands for the western world is credited to King Juba II (f. ca. 48 BCE–23 CE), the Berber king of Numidia. He ruled from 29 to 27 BC and later became the vassal king of Mauretania under Roman control from 25 BC to 23 AD. Juba II established a close alliance with Rome and was known for his loyalty to the empire. According to Pliny the Elder, Juba II dispatched an expedition to the Canary Islands. The explorers did not encounter any native inhabitants but found several buildings as evidence of past habitation. Juba II named the islands after the ferocious dogs he encountered there, which may have been seals or the dog-like creatures worshipped by the indigenous people.

Pliny states that the Isles of Bliss, as Juba II called them, are located in a southwestern direction, approximately 625 miles away from the Purple Islands. The first island they reached was called Ombrios, featuring a pool surrounded by mountains and trees resembling giant fennel. The second island, Junonia, had a small temple made from a single stone. Nearby, there was a smaller island with the same name, followed by Capraria, known for its large lizards. The islands of Ninguaria and Canaria were also visible, with Ninguaria covered in perpetual snow and clouds and Canaria named due to its abundance of huge dogs. Juba II brought two of these dogs back with him. The islands were described as having an ample supply of fruit, various bird species, palm groves with dates, coniferous trees, honey, papyrus growing in rivers, and sheatfish. Pliny also mentions the islands being plagued by the carcasses of monstrous creatures washed ashore by the sea. This account by Pliny the Elder provides insights into Juba II's exploration of the Canary Islands and provides descriptions of the islands' landscapes, flora, fauna, and natural resources.

Sallust's narrative provides four surviving fragments about the Fortunate Isles. The narrative recounts that according to Sallust, two neighboring islands, located ten thousand stades from Gades (Cádiz), were known to produce food for humans without any human intervention, and it says that philosophers believe that Elysium, the mythical place of bliss, corresponds to the Fortunate Isles mentioned by Sallust, which gained fame through the songs of Homer. According to the narrative, Sallust mentions that there were plans of venturing into distant parts of the Ocean, presumably in search of the Fortunate Isles, and that the desire to explore the unknown seems to have driven this pursuit, as humans are naturally inclined to seek unfamiliar experiences.

The Greek geographer Strabo makes mention of the Isles of the Blest and their proximity to Maurusia and Iberia (known as Mauretania and Hispania in Roman by the Romans). He describes these islands as being situated on the far western side of Maurusia, along the coast that runs parallel to Spain. Strabo suggests that he considered these regions, due to their proximity to the islands, to be blessed as well. He further notes that the islands are located near the promontories of Maurusia, which are opposite the city of Gadir (Cádiz). Strabo's accounts shed light on the geographical understanding and perception of the Isles of the Blest in relation to Maurusia and Iberia during his time.

Pomponius Mela, an early Roman geographer, provides a description of the Fortunate Islands (Isles of Bliss) that sheds light on the reasons behind their name. Born in Tingentera (modern Algeciras, Spain), Mela describes the Fortunate Isles as having a sandy landscape and an abundance of spontaneously generated plants. These islands are known for their continuous production of various fruits, creating an environment where inhabitants lack nothing and enjoy greater productivity than other places. One of the islands gains particular fame due to the uniqueness of its two springs. Drinking from one of these springs is said to cause uncontrollable laughter, while the other spring serves as a cure for those affected by the laughter-inducing spring. Mela's description emphasizes the fertile and prosperous nature of the Fortunate Islands, highlighting the reasons behind their reputation as a place of abundance and happiness.

Plutarch's writings provide insights into the Fortunate Isles, also known as the Isles of the Blessed, located in the Atlantic Ocean. In his work Vita Sertorii, Plutarch recounts an encounter between Sertorius, a Roman general, and sailors who had recently visited these islands. The Fortunate Isles are described as a few days' sail from Hispania (modern-day Spain), known for their idyllic qualities and natural paradise characterized by mild weather and abundant fertility. Plutarch equates these islands with the mythical Elysian Fields, a place of happiness and bliss. The climate on the islands is pleasant, with moderate seasonal changes and no extreme weather. The winds from the Roman side dissipate before reaching the islands, while the South and West winds bring occasional showers and cool, moist breezes that nourish the land. Plutarch mentions that even barbarians believe these islands to be the Elysian Fields. Sertorius, upon hearing about the islands, develops a strong desire to retire there and escape from perpetual wars and tyranny. However, he ultimately does not act on this desire and returns to Hispania at the request of the Lusitanians, who sought him as their leader.

The Greek geographer Claudius Ptolemy lists the Fortunate Islands, which he says to be six. The Romanized forms of the emended names for the islands are given below:

The islands near Libya lie in the Western Ocean […] and these are the Islands of the Blessed Inaccessa Island Pluitana Island Capraria Island Nivaria Island Juno’s Island Canaria Island — Claudius Ptolemy, Geographia, Book IV, Chapter 6 - ca. 150 CE

Ptolemy used these islands as the reference for the measurement of geographical longitude and they continued to play the role of defining the prime meridian through the Middle Ages.

Flavius Philostratus provides information about the location of the Fortunate Isles. According to him, the Islands of the Blessed, synonymous with the Fortunate Isles, are believed to be situated near the boundaries of Libya, where it extends towards an uninhabited promontory.

Gaius Iulius Solinus presents a differing opinion on the Fortunate Islands, acknowledging their celebrated name while expressing skepticism about their actual nature. Solinus recognizes the existence of three Fortunate Islands, but believes that their fame surpasses their reality. He describes the first island, Embrion, as devoid of buildings, with reeds growing to tree-like proportions. Squeezing the black reeds yields a bitter liquid, while the white reeds release drinkable water. Solinus mentions another island called Iunonia, featuring a small temple with a low pointed roof. The neighboring third island shares the same name and is barren. The fourth island, Capraria, is densely populated with large lizards. Nivaria, the fifth island, is characterized by thick, cloudy air, resulting in constant snowfall. Canaria, the sixth island, is known for its distinctive dogs. Traces of buildings remain, and the island is abundant with birds, fruit-bearing forests, palm groves, pine nuts, honey, and rivers teeming with sheatfish. Solinus also notes the belief that the sea surrounding Canaria ejects sea monsters onto its shores, causing a foul odor when the decomposing monsters taint the surroundings. Overall, Solinus concludes that the nature of the islands does not fully align with their renowned name.

Identification of the islands mentioned by ancient authors

The names the ancient authors mention have traditionally been assigned to all seven large islands of the Canaries. However, Ptolemy and Juba only mention six islands, suggesting that one of the large islands is not mentioned or that multiple large islands are missing. It is possible that the islets in the eastern part of the archipelago should be considered as well.

The winterless climate and ideal conditions for fruit-bearing trees that the ancient authors spoke of gave the Fortunate Islands their name. This feature applies to the central and western islands, but not to the eastern islands of Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, whose low height makes them unable to reach the moisture-rich trade winds. Apparently, this was considered by authors such as Sebosus, Sallust and Plutarch, who did not include the eastern islands in the Fortunate Islands.

Roman presence on the islands

It is not entirely certain whether the Romans established any permanent centre on the islands. However, in 1964, Roman amphorae were discovered off the coast of Lanzarote, proving that at least trade existed with the Romans. In the 1990s, at the archaeological site of El Bebedero near Teguise, also in Lanzarote, numerous fragments of Roman ceramics, glass and metal dating to the 1st-4th century CE were found. Retail material testing proved that those could come from Campania in Italy, or the Roman provinces of Hispania Baetica and Africa. Lastly, in 2012, a fragment of a Roman amphora was found near La Concha beach on the tiny Islote de Lobos, located between Lanzarote and Fuerteventura. Since then, houses, ceramics, tools and other everyday artifacts have been found on the islet. Moreover, remains of purple dye have been found at the beach of La Calera, as well as a large amount of fractured shells of Stramonita haemastoma (> 95%) and Hexaplex duplex—both species of the family Muricidae that produce a purple dye—with anthropic fracture patterns. The Islote de Lobos, therefore, seemed to have housed a Roman factory dedicated to the extraction of the Gaetulian purple dye found in the mucus of these molluscs, similar to the one on the Insulae Purpurariae or "Purple Islands" established by Juba II, probably to be identified with Mogador, near Essaouira on the Moroccan coast.

Extracting this dye involved tens of thousands of snails and substantial labour from the gatherers, specifically called mūrĭlĕgŭlī in Latin (from murex-legulus, literally "rock snail gatherer"), hence purple dye was highly valued. According to the 4th century BCE historian Theopompus "purple dye fetched its weight in silver at Colophon". Purple-dyed textiles became status symbols: the most senior Roman magistrates wore a toga praetexta, a white toga edged in purple; the even more sumptuous toga picta, a solid purple toga with gold thread edging, was worn by generals celebrating a Roman triumph. By the 4th century CE, however, it was reserved exclusively for the emperor—with citizens facing death penalty if they wore any shade of the colour.

Early and High Middle Ages

For a thousand years, between the 4th and 14th centuries, the islands seem to disappear from the historical record and fall into obscurity. Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, the ties between Mediterranean civilizations and the Canary Islands weakened but were perhaps not completely severed. The only documentary evidence of this time—though unreliable—is the journey of Saint Brendan the Navigator (f. 484–c. 577 CE) and accounts from Muslim geographers from the 10th and 12th centuries that mention islands in the Sea of Gloom, which might correspond to some of the Canary Islands.

Saint Brendan’s legendary journey to the Promised Land for Saints

Saint Brendan is primarily known for his legendary journey to a blessed island. Brendan's journey was popular throughout Christian Europe for many centuries. The voyage is believed to have taken place between 512 and 530 CE, with the earliest recorded version of the narrative dating to around 900 CE. Over 140 manuscripts of the narrative exist with numerous translations.

The mythical island of Saint Brendan, also known as Isla de San Borondón, was depicted on medieval and renaissance maps. Its geographical location has been subject to various interpretations, ranging from being placed southwest of Ireland to being west of the Canary Islands or even further out beyond the Azores. The legend gained widespread recognition in Europe during the Middle Ages, and maps from Christopher Columbus' era often featured an island labeled as Saint Brendan's Isle in the Atlantic Ocean. Several naval expeditions were even undertaken in search of the promised land of Saint Brendan. However, belief in the physical existence of the island diminished by the 19th century.

The journey of Brendan begins when he meets Saint Barinthus, who describes the "Promised Land for Saints." Inspired by this description, Brendan gathers a group of monks and sets off on a voyage. They encounter various islands, including one where a companion dies, the Island of Sheep, and a giant fish named Jasconius. They also visit the Island of Birds, the Island of Ailbe with silent monks, and the Island of Strong Men. After seven years of travel, they finally reach the blessed island, are briefly allowed to enter, and then return to Ireland passing through another fabled island.

The written account of Brendan's voyage has been seen as a religious allegory, although there has been substantial debate regarding the extent to which these legends are based on historical events. The legend mentions islands which potentially correspond to the Canary Islands. Juan de Abréu Galindo suggests that the Island of Saint Brendan is the eighth of the Canary Islands and equates it with Ptolemy's Inaccessa Island.

Possible Muslim expeditions

During the High Middle Ages, Arabic sources hinted at the existence of the Canaries, referring to certain Atlantic islands that were speculated to be the Canaries. Although the ancient Canarians were possibly no longer isolated, they maintained cultural isolation and preserved their distinct way of life.

Arab scholars al-Masʿūdī from the 10th century and al-ʾIdrīsī from 12th century learned about the Canary Islands through their study of Ptolemy's work, giving them their own name in Arabic. They name two islands in Arabic which might correspond to two of the Canary Islands, along with enormous creatures and mysterious phenomena. Also recounted are the risks and curiosities of the Atlantic Ocean, with some adventurers returning safely and others perishing in their attempts. Among the successful endeavours was maritime expedition by a family of Andalusi seafarers, who discovered previously unknown land, and encountered an inhabited island with red-skinned people during their journey through the Atlantic, who might have been the ancient Canarians, and by whom they were taken prisoners. They were eventually welcomed back by the Berber people in present-day Morocco.

Berber kingdoms prior to the Castilian conquest

As the Berbers who arrived in the Canary Islands adapted to the diverse habitats of each island, they gradually became isolated on their respective lands. Over time, they developed into seven distinct cultures, each unique to its own island. These cultures possessed their own distinct religious beliefs, as well as social, political, and economic structures.

Their adaptation to the islands and their habitats can be inferred from their rock art, with later rock art being simpler and with less variations than the more ancient ones. Possibly, their initial lack of knowledge of the island's environments and its limited resources compelled them to perform shamanic practices that were meant to promote rainfall or fertility, which were no longer essential as they adapted to their new environments.

[The territorial division of the Canary Islands at the time of the Castilian conquest with the reconstructed names of the islands in Berber.][nombres bereberes de las Islas Canarias, nombres guanches de las Islas Canarias, Berber names of the Canary Islands, Guanche names of the Canary Islands]

Gran Canaria

Castilianised Berber: Tamarán

Insular Berber: *Tamāran

Tamarán before the unification under Atidamana and Gumidafe.

Tamarán after Taghoter Semidán's division of the island between his two sons.

Before the arrival of the Norman conquerors in 1402, the island was divided into numerous independent territories ruled by tribal chiefs. The order between the cantons, that tended to wage war on eachother for pasture, was maintained by a woman named Atidamana, who was respected by the population and assumed the role of judge in the conflicts and high priestess. However, some chiefs did not want to obey Atidamana's decisions, and argued that they shouldn't be subdued by a woman. Therefore, Atidamana married a warrior chief from Gáldar named Gumidafe, and together waged war on the rest of the chiefs until finally achieving complete control over the island and unifying the government, becoming guanartemes (kings).

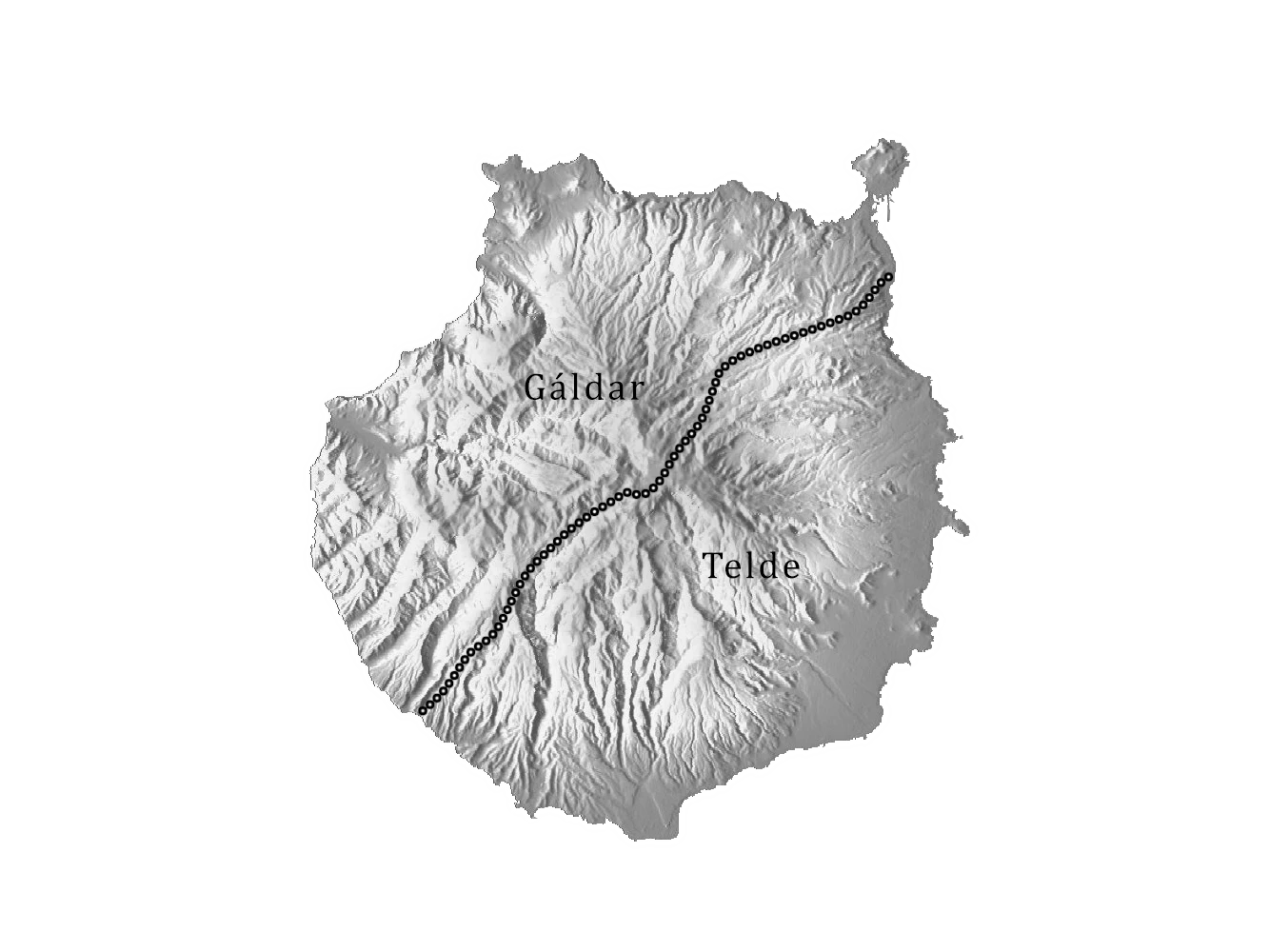

Atidamana's and Gumidafe's grandson Taghoter Semidán divided the island in 1440, or earlier, between his two sons, and two guanartemates (kingdoms) were founded. Guanache Semidán inherited Gáldar and Bentanguaire Semidán inherited Telde. The frontier lied along the Barranco Guiniguada and the Barranco de Mogán or Barranco de Arquineguín. The sábor (council) however would remain in Gáldar and ended up triggering confrontations. Before the arrival of Castilian conquerors in 1478, the island is virtually unified once again due to the death of the two kings, and Tenesor Semidán is named king, who defended Bentejuí's right to rule in Telde.

Tenerife

Castilianised Berber: Achineche

Insular Berber: *Ašenšen

Tinerfe the Great, also called Betzenuria, was the last mencey (king) of Achineche that ruled over the entire island. He lived in Adeje, like all his predecessors, in the late 14th century, approximately hundred years before the conquest of 1494 by Castile. Upon his death, his sons divided the islands into nine menceyates. Some historians believe the name of the island of Tenerife could derive from his name. Others state that the first author to call him Tinerfe, the poet Antonio de Viana, invented the name in 1604, and that his real name was Betzenuriia.

Muchos años estuvo esta isla y gente della sujeta a un solo rey, que era el de Adeje, cuyo nombre se perdió de la memoria, y como llegase a la vejez, a quien todo se le atreve, cada cual de sus hijos, que eran nueve, se levantó con su pedazo de tierra, haciendo término y reino por sí.Translation:For many years, the island and its people were subject to one king, who was from Adeje, whose name is lost from memory, and when he became of old age, each of his sons, that were nine, rose with their own piece of land, making for themselves a kingdom.— Friar Alonso de Espinosa, Historia de Nuestra Señora de Candelaria

En esta isla de Tanerife hubo un señor que la mandaba y á quien obedecian que se llamaba Betzenuriia [...] el qual tenia nueve hijos, y muerto el padre cada uno se alzó con la parte que pudo y entre si se conformaron y la repartieron, y de un reyno que era se dividió en nueve. El mayor de todos estos hermanos se llamaba Imobac, cuyo señorio y reyno se decia Taoro [...] Acaymo su hermano, se instituló rey de Aguimar; Atquaxona, rey de Abona; Atbitocarpe, rey de Adeje. Los demás nombres de estos hermanos se han perdido en la memoria de ellos."Translation:On this island of Tenerife there was a lord that ruled it and who was obeyed, who was called Betzenuriia [...] who had nine sons. Upon their father's death, each one rose up with the part that they could and divided it; and, from one kingdom, nine were formed. The greatest of these brothers was called Imobat, whose kingdom was called Taoro [...] Acaymo, his brother, made himself king of Aguimar; Atquaxona, king of Abona; Atbitocarpe, king of Adeje. The names of the remaining brothers have been lost to their memory.— Juan de Abreu Galindo, Historia de la Conquista de las Siete Islas de Gran Canaria, Libro III, Capítulo XI – 1602

All the classical authors agree that there was one absolute king with residence in Adeje, upon whose death the island was divided between his nine sons: Acaymo, Atbitocazpe, Atguaxoña, Benecharo, Betzenuhya, Caconaimo, Chincanairo, Rumen y Tegueste. According to the historian and physician Juan Bethencourt Alfonso, Tinerfe was son of mencey Sunta, succeeding him as king of the island upon his death. However, his uncles attempted to overthrow him. Bethencourt states that Tinerfe "reformed the tactic of his father and was the founder of strategy, and Tenerife achieved great prosperity under his prolonged reign."

La Palma

Castilianised Berber: Benahoare

Insular Berber: *Wen-Ahūwwār

Friar Juan de Abréu Galindo provides an account of the bellicose history of Benahoare before the Castilian conquest. Aktanasut, or as he was known by the Castilians, Tanausú, ruled the canton of Aceró within the Caldera de Taburiente. According to this historian, Atogmatoma, the ruler of Tijarafe, had a conflict with Tanausú. Atogmatoma entered the Caldera with 200 men through Adamancasis (now known as El Riachuelo, near La Cumbrecita), but Tanausú and his men managed to repel the attack. With the help of his relatives Bediesta and Temiaba, lords of Tegalguen and Tagaragre, Atogmatoma later entered the Caldera. Tanausú then takes refuge in Mount Bejenado and sought aid from his cousins Ehenauca, Mayantigo, Azuquahe, Juguiro and Garehagua. Once all the warriors were rallied, Tanausú and his forces descended to the plain of Adirane, where they defeated Atogmatoma. Atogmatoma was spared, and his daughter Tinabuna was married to Aganeye, one of Tanausú's allies. The conflict between Tanausú and Atogmatoma eventually led to a peace agreement, and they celebrated the wedding, remaining as friends.

Benahoare was divided into 12 cantons at the time of the arrival of Castilian conquerors. As opposed to Achineche or Tamarán, it had no territorial unit above it. In fact, this system was not permanent and these units could be further divided into smaller ones, like the Gazmira band which is mentioned in the 16th century. The last canton to be conquered by Castile Aceró, located in the Caldera de Taburiente. The name is believed to mean "strong place", and indeed the Caldera lends itself to a strong defense, measuring 10 km across and possessing steep walls towering up to 2000 m over the caldera floor.

Pre-conquest exploration

The Canary Islands saw an increase in visits during the late 13th century due to various factors.

Firstly, it was propelled by the economic growth of European states like the Republic of Genoa, the Crown of Aragon, the Kingdom of Castile, and the Kingdom of Portugal. These nations were already involved in maritime trade along the Moroccan coast, and their expansionist ambitions naturally turned towards the Canary Islands.

Secondly, advancements in navigation techniques, including the use of the compass, astrolabe, stern rudder, and cog-caravel, played a pivotal role. These innovations, coupled with the development of cartography, allowed for more accurate and detailed maps. Notably, Angelino Dulcert of Majorca created a portulan map in 1339 that depicted some of the Canary Islands. It was around this time that the islands were effectively rediscovered by the Genoese sailor Lanzarotto Malocello. In 1341, just two years later, the first expedition to visit all the islands of the archipelago was conducted under the command of another Genoese seaman and explorer, Niccoloso da Recco, on behalf of Portuguese king Afonso IV.

Lastly, both ideological and political motives played a significant role. The Southern European monarchies were in an expansionist phase, with the Iberian monarchies driven by the Reconquista (the reconquest) of Muslim-controlled regions in southern Spain, known as al-ʾAndalus (Arabic: ٱلْأَنْدَلُس), with kings such as Alfonso XI of Castile claiming that, by the ancient Visigothic dioceses and Reconquista treaties, the islands fell within the Castilian jurisdiction and "sphere of conquest". The territorial expansion served to strengthen royal power and was infused with a crusader and missionary spirit.

These combined factors led to an increased interest in and exploration of the Canary Islands during this period, setting the stage for further European presence and, ultimately, the Castilian conquest of the archipelago.

Genoese contact

In the 14th century, the "rediscovery" of the islands by Europeans took place, with numerous visits by Genoese, Majorcan, Portuguese and Castilian, competing for control of the Canaries. This process falls within the so-called European expansion across the Atlantic, which, in its initial stage, had as its main motivation the most direct possible access to the gold of central Africa.

The first European to visit the Canary Islands since Antiquity was a Genoese captain by the name of Lancelotto Malocello embarked on a voyage believed to have taken place around 1318-1325, though traditionally dated as 1312. The exact motivations behind Malocello's journey remain somewhat unclear, with some speculating that he was in search of the Vivaldi brothers who had disappeared off the coast of Morocco near Cape Non in 1291. Upon reaching the Canary Islands, Malocello made landfall, possibly due to a shipwreck, on the island of Lanzarote and decided to remain there for nearly two decades. During his time on the island, it is believed that Malocello may have attempted to establish himself as a ruler among the indigenous people, but eventually he was expelled by a revolt led by Zonzamas.

In 1339, a portolan map created by Angelino Dulcert of Majorca depicted the island of Lanzarote, referred to as Insula de Lanzarotus Marocelus and marked with a Genoese shield. This map also showcased the neighboring islands of Forte Vetura (Fuerteventura) and Vegi Mari (Islote de Lobos). While earlier maps had depicted fantastical depictions of the "Fortunate Islands" based on references in Pliny's writings, Dulcert's map was the first to present a more accurate representation of the actual Canary Islands. It should be noted, however, that Dulcert included some fictional islands on the map, such as Saint Brendan's Island (Spanish: Isla de San Borondón), as well as three islands named Primaria, Capraria, and Canaria, inspired by the names provided by the ancient authors.

In 1341, a significant expedition sponsored by King Afonso IV of Portugal set sail from Lisbon. Commanded by Florentine captain Angiolino del Tegghia de Corbizzi and Genoese captain Nicoloso da Recco, the expedition consisted of a diverse crew comprising Italians, Portuguese, and Castilians. Over the course of five months, the expedition meticulously surveyed the archipelago, mapping thirteen islands, including seven major ones and six minor ones. They also studied the indigenous inhabitants and brought back four natives to Lisbon. This expedition served as the foundation for later Portuguese claims of priority and influence over the Canary Islands.

Cerda lordship of Fortuna

The islands were under the watchful eye of the kings of Castile, with Pope Clement VI appointing the Castilian-French noble Infante Luis de la Cerda, the Count of Clermont, Admiral of France and expatriate royal prince of the Crown of Castile, as the prince of the Principality of Fortune in 1355, even though he never actually set foot on the islands.

The exploration of the Canaries in the 14th century sparked rapid European interest, especially after the mapping expedition of 1341. The accounts of the aboriginals captured the attention of European merchants, who saw the potential for lucrative slave-raiding opportunities. In 1342, multiple expeditions were organized from Majorca, with Francesc Duvalers and Domenech Gual leading separate ventures commissioned by private merchant consortia under the authority of Roger de Robenach, the representative of James III of Majorca. There may have been as many as four or five expeditions commissioned from Majorca that year, although the outcomes of these endeavors remain uncertain.

The Catholic Church was also intrigued by the news coming from the Canaries. In 1344, the Castilian-French nobleman Infante Luis de la Cerda, the Count of Clermont, Admiral of France and expatriate royal prince of the Crown of Castile, who served as a French ambassador to the papal court in Avignon, presented a proposal to Pope Clement VI. His plan envisioned the conquest of the islands and the conversion of the native Canarians to Christianity. In November 1344, Pope Clement VI issued the bull Tuae devotionis sinceritas, granting perpetual possession of the Canary Islands to Luis de la Cerda and conferring upon him the title of "Prince of Fortuna." The pope further declared the projected conquest and conversion as a crusade, granting indulgences to its participants. Papal letters were sent to the monarchs of the Iberian Peninsula, urging them to provide material support to Cerda's expedition. King Afonso IV of Portugal lodged a protest, claiming prior discovery rights, but ultimately accepted the pope's authority. Alfonso XI of Castile also voiced objections, asserting that the islands fell within Castilian jurisdiction based on ancient Visigothic dioceses and prior treaties of reconquest. However, he recognized Cerda's title.

Despite the formal recognition of Cerda's title, the Iberian monarchs hindered the organization of his expedition, causing delays. Consequently, no expedition to the Canary Islands materialized before the death of Luis de la Cerda on July 5, 1348. According to the terms of the 1344 contract, the lordship of Fortuna was set to expire after five years without an expedition, although Cerda's heirs, the Counts of Medinacelli, would later revive their claim.

Majorcan-Aragonese contact

The Majorcans established a mission on the islands (Bishopric of Telde), which remained active from 1350 to 1400.

After the demise of Cerda, the previous actors resumed their ventures, but historical records for the following generation are scarce. However, there are mentions of three additional expeditions by Majorcans, who were now under Aragonese rule since 1344. The renowned expedition of Jaume Ferrer in 1346 aimed to reach the "River of Gold" (Senegal) on the African coast but may have also touched the Canaries en route. In 1352, Arnau Roger led an expedition to Gran Canaria, and in 1366, Joan Mora undertook a royal-sponsored patrol expedition. Undoubtedly, there were numerous unrecorded expeditions, not only by Majorcans but also by merchants from Seville and Lisbon. These expeditions primarily had commercial motives, often involving the capture of native islanders for the European slave trade. However, there was also some peaceful trade with the locals, particularly for orchil and dragon's blood, which were highly valued as dyes in the European textile industry.

Although the Cerda project failed, the Pope remained committed to converting the natives. In 1351, Pope Clement VI endorsed an expedition by Majorcan captains Joan Doria and Jaume Segarra. The objective was to bring Franciscan missionaries, along with twelve converted Canarian natives who had been seized by previous Majorcan expeditions, to the islands. It is uncertain if this expedition ever took place, but it is likely that it was incorporated into Arnau Roger's expedition in 1352. According to apocryphal legend, the Majorcan missionaries successfully established an evangelizing center in Telde (on Gran Canaria) until they were massacred by the natives in 1354.

To support the missionaries in Telde, the Pope established the 'Diocese of Fortuna' in 1351, although this appears to have been a nominal appointment. Papal interest in the Canaries diminished after the death of Pope Clement VI in late 1352. The next generation provides very little information about the Canary Islands. It is probable that the Majorcans and Aragonese maintained their commercial interests, primarily focused on Gran Canaria, but there are few records.

The next mention of the Canary Islands occurs in 1366 when King Peter IV of Aragon commissioned Captain Joan Mora to patrol the islands, assert Aragonese sovereignty, and deter interlopers. Though there was still no plan for conquest, the interest in establishing missionary centers seemed to revive. In July 1369, Pope Urban V issued a bull establishing the Diocese of Fortuna and appointing Fr. Bonnant Tari as bishop. In September 1369, another bull instructed the bishops of Barcelona and Tortosa to dispatch 10 secular and 20 regular clergy to preach to the Canarians in their native languages. However, it is uncertain if these plans were realized or remained merely theoretical. A more reliable account is available for a Majorcan expedition in 1386 sponsored by Peter IV of Aragon and Pope Urban VI, carried out by the "Pauperes Heremite." Though their exact fate is unknown, a later report indicates that thirteen "Christian friars" who had been preaching in the Canaries for seven years were massacred during an uprising in 1391. Between 1352 and 1386, at least five missionary expeditions were sent or planned.

Geographical knowledge of the Canary Islands expanded with these expeditions. The 1367 portolan chart created by the Pizzigano brothers depicts eight of the Canary Islands, including La Gomera and El Hierro. The Catalan Atlas of 1375, a few years later, provides an almost complete and accurate map of the Canaries (with the exception of La Palma). The Catalan Atlas names the eleven islands from east to west as Graciosa (La Graciosa), laregranza (Alegranza), rocho (Roque), Insula de lanzaroto maloxelo (Lanzarote), insula de li vegi marin (Lobos), forteventura (Fuerteventura), Insula de Canaria (Gran Canaria), Insula del infernio (Tenerife), insula de gomera (La Gomera), insula de lo fero (El Hierro). The name 'tenerefiz' is first mentioned alongside 'Infierno' in the 1385 Libro del Conoscimiento.

Portuguese contact

Amidst the Fernandine Wars, a series of conflicts between Portugal and Castile following the assassination of Peter I of Castile, both Portuguese and Castilian privateers found themselves entangled in hostilities. It was during this tumultuous period in the 1370s that some of these privateers sought refuge or embarked on slave-raiding expeditions to the Canary Islands.

In a noteworthy development signaling a renewed interest in conquest since 1344, King Ferdinand I of Portugal granted the islands of Lanzarote and La Gomera to an audacious adventurer known as 'Lançarote da Franquia' (some speculate that this enigmatic figure was none other than the seemingly ageless Lanceloto Malocello). Lançarote da Franquia endeavored to seize control of the islands and reportedly engaged in skirmishes with both the indigenous Guanches and Castilian forces by 1376. However, it appears that the Portuguese attempt to establish a foothold faltered following Lançarote's demise in 1385.

Castilian contact

The Canary Islands initially captured the interest of the Majorcan-Aragonese during the 1340s-60s, with a particular focus on Gran Canaria. The Portuguese also displayed a burgeoning fascination with the archipelago in the 1370s-80s, concentrating their efforts on Lanzarote. While there are vague references to Castilian adventurers preceding these endeavors, it was only after 1390 that Castile truly emerged as a significant player in the region.

In 1390, Gonzalo Peraza Martel, the Lord of Almonaster and a prominent figure from Seville, sought permission from King Henry III of Castile to embark on a conquest of the Canary Islands. Joining him in this ambitious undertaking was the Castilian nobleman Juan Alonso de Guzmán, the Count of Niebla.

A fleet of five ships was assembled, crewed by Andalusians from Seville and intrepid Basque adventurers hailing from Vizcaya and Guipuzcoa. In 1393, the Almonaster expedition departed from Cadiz, traversing the Canary Islands and surveying the coastlines of Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria, Hierro, Gomera, and Tenerife. Ultimately, they chose to make landfall on Lanzarote, conducting a raid that resulted in the capture of approximately 170 indigenous inhabitants, including the local Guanche king and queen. Additionally, they obtained a significant haul of skins, wax, and dyewood, which they sold in Seville, reaping substantial profits.

Upon their return to Castile, Almonaster and Niebla presented their captives and acquired goods before King Henry III, emphasizing the ease of conquering the Canary Islands and the immense profitability they offered. This report heightened the ambitions of other adventurers who now sought to make their mark in the region.

Legends

Throughout the 14th century, various purported expeditions to the Canary Islands have been recorded, some of which have been revealed as apocryphal or intertwined with other voyages, as later determined by Fr. Juan de Abreu Galindo (1632) and Viera y Clavigo (1772). Among the legendary accounts are the following:

In the year 1360, a Majorcan expedition consisting of two ships, led by an unknown captain (rumored to be the same Aragonese galleys prepared for Cerda in 1344), is said to have landed at either La Gomera or Gran Canaria. According to legend, the European explorers were defeated and taken captive by the indigenous Canarians. After residing among the Canarians for a certain duration, the native chieftains secretly decided to execute all the prisoners. The entire crew, including the clerics (two Franciscan friars according to Abreu de Galindo, five as stated by Viera y Clavijo), were swiftly rounded up and massacred by the Canarians (likely confused with the 1351 Majorcan expedition).

In 1372, an expedition led by 'Fernando de Castro' (a Galician, not to be confused with his Portuguese namesake) also made landfall at La Gomera. After engaging in hostilities, Castro was defeated by the native inhabitants. However, unlike the 1360 expedition, the surviving Europeans were mercifully spared and allowed to return to Iberia. Legend has it that at the request of the local king Amalahuige, Castro (or Ormel later on) left behind his chaplain to undertake the conversion of his people to Christianity.

The well-known tale of the Biscayan privateer Martín Ruiz de Avendaño unfolds in 1377 when he sought refuge on Lanzarote. During his stay, he allegedly entered into a romantic relationship with Queen Fayna, the wife of native king Zonzamas. This liaison resulted in the birth of a daughter named Ico, who eventually married the succeeding king Guanarame and bore a son named Guadarfia. However, suspicions arose following Guanarame's death, questioning the noble lineage of Ico (Avendaño's daughter), which led to a trial by ordeal in the form of being sealed in a smoke-filled hut, which she miraculously survived.

In 1382, a ship hailing from Seville, commanded by Francisco Lopez, encountered a shipwreck near Guinigada (Gran Canaria), leaving only 13 survivors. These survivors integrated into Canarian society and lived among the native population until their deaths around 1394.

Hernán Peraza, a Sevillian with authorization from Henry III of Castile, embarked on an expedition in 1385 that raided Lanzarote (likely a case of mistaken identity with the Almonaster raid of 1393).

In 1386, a two-ship expedition led by Fernando de Ormel, a nobleman from Galicia and a naval officer of John I of Castile, set sail. While patrolling the Andalusian coast, they encountered a storm that unexpectedly led them to emerge at La Gomera (possibly the same expedition as Castro's in 1372).

A 1399 expedition led by Gonzalo Peraza Martel, Lord of Almonastor, conducted a raid on Lanzarote (possibly confused with the Almonaster raid of 1393).

Castilian conquest of the Canary Islands (1402–1496)

The conquest of the Canary Islands spanned from 1402 to 1496, and it proved to be a challenging endeavor both militarily and politically. The indigenous Guanche people fiercely resisted the invaders in certain islands, posing significant military obstacles. Furthermore, the conquest encountered political complexities due to conflicting interests between the nobility, who sought to bolster their economic and political influence, and the state, particularly Castile, which aimed to consolidate its power and compete with the nobles. This clash of interests added another layer of difficulty to the conquest process.

Aristocratic conquest or conquista señorial (1402–1476)

In this first phase, the conquest of the Canary Islands was carried out by private individuals, not by the Crown, which is why it is called the aristocratic conquest. The aristocratic conquest included the islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, La Gomera, and El Hierro: these were the least populated islands of the archipelago, and their surrender was relatively straightforward. However, La Gomera maintained a mixed organization in which conquerors and indigenous people agreed to coexist until the so-called "Rebellion of Los Gomeros" in 1488, which led to the effective conquest of the island.

Norman aristocratic conquest or conquista señorial betancuriana o normanda

In 1402, the conquest truly began with the expedition to Lanzarote by the Normans Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de la Salle, on behalf of the Crown of Castile. Their primary motivation was economic, as Béthencourt, who owned textile factories and dye works, saw the Canaries as a source of valuable dyes like orchil, a lichen which produces orcein, from which a purple dye can be obtained, and that grows on the windward facing cliffs of the islands which receive moist air from the trade winds.

Bethencourt received crucial political support from King Henry III of Castile. His uncle, Robert de Bracquemont, obtained the king's permission for Bethencourt to conquer the Canary Islands on behalf of the Norman noble. In exchange, Bethencourt became a vassal of the Castilian king. Robert de Bracquemont invested a significant amount in the venture. The chronicle known as Le Canarien, compiled by clerics Pierre Bontier and Jean Le Verrier, documented the story of Béthencourt's conquest. Two later versions, one by Gadifer de La Salle (considered more reliable) and the other by Béthencourt's nephew, Maciot de Béthencourt, adapted the original account.

The conquest of Lanzarote

The Norman expedition departed from La Rochelle and made stops in Galicia and Cádiz before reaching Lanzarote in the summer of 1402. The island's indigenous population, led by their chief Guadarfia, could not withstand the invading forces and surrendered. The Normans established themselves in the south of the island, constructing a fortress and founding the Bishopric of Rubicon. From this base, they launched an attack on Fuerteventura.

The conquest of Fuerteventura

This campaign lasted from 1402 to 1405. The prolonged duration was not primarily due to resistance from the islanders but rather to difficulties and internal divisions between the two captains leading the invaders. Hunger and limited resources forced the expedition to retreat to Lanzarote. Jean de Bethencourt traveled to Castile to secure further support, and King Enrique III provided the necessary assistance and confirmed Béthencourt's exclusive rights to conquer the island, sidelining Gadifer.

During Béthencourt's absence, Gadifer faced a dual rebellion. One faction of his men, led by Bertín de Berneval, resumed capturing slaves, while the Lanzarote Guanches resisted this practice. Pacifying the island took until 1404, and the conquest of Fuerteventura recommenced at the end of that year. However, the two commanders operated independently, each fortifying their respective domains (the castles of Rico Roque and Valtarajal). The island's conquest was completed in 1405 when the native kings surrendered. Gadifer eventually abandoned the island, never to return.

After the victory, Béthencourt, as the outright owner of the islands, returned to Normandy to recruit settlers and gather resources for the continued conquest of the remaining islands.

Castilian aristocratic conquest or conquista señorial castellana

The Bethencourt era concluded in 1418 when Maciot sold his holdings and the rights to subjugate the remaining islands to Enrique Pérez de Guzmán. From this point onward, the involvement of the King of Castile increased. Between 1418 and 1445, control over the islands changed hands multiple times. Eventually, Hernán Peraza the Elder and his children Guillén Peraza and Inés Peraza gained dominion over the conquered islands and the right to further conquests. The death of Guillén Peraza in the attack on La Palma was immortalized in a sorrowful lament. After her brother's death, Inés and her husband Diego García de Herrera became the sole rulers of the islands until 1477 when they ceded La Gomera to their son Hernán Peraza the Younger and the rights to conquer La Palma, Gran Canaria, and Tenerife to the King of Castile.

The island of La Gomera was peacefully incorporated into the Peraza-Herrera fiefdom through an agreement between Hernán Peraza the Elder and some of the island's aboriginal groups who accepted Castilian rule. However, there were several uprisings by the Guanches due to the mistreatment of the native Gomeros by the rulers. The last major rebellion occurred in 1488 and resulted in the death of Hernán Peraza the Younger, the ruler of the islands. His widow, Beatriz de Bobadilla y Ossorio, assumed power and sought the assistance of Pedro de Vera, the conqueror of Gran Canaria, to suppressthe rebellion. The subsequent repression led to the death of two hundred rebels, with many others being sold into slavery in the Spanish markets.

Royal conquest or conquista realenga (1478–1496)

The second phase of the Spanish conquest of the Canaries, at the behest of the Catholic Monarchs, diverged significantly from its predecessor. Meticulously organized and equipped, the invading forces stood as a formidable military presence at the forefront of the conquest. Financing for this ambitious endeavor was shouldered jointly by the Crown and individuals driven by a fervent desire to exploit the islands' resources.

However, the indigenous population of all three islands, particularly on Gran Canaria and Tenerife, fiercely resisted the conquest. The aboriginals, resolute in their commitment to defend their ancestral lands, posed a formidable challenge to the Spanish forces. Their resistance, marked by both bravery and resilience, would prove to be a protracted struggle.

The royal conquest phase was initiated following the relinquishment of rights over Gran Canaria, La Palma, and Tenerife by the island lords in 1477. This marked the onset of the most arduous phase, as these territories were the most populous, organized, and featured challenging terrain. The conquest of Gran Canaria commenced in 1478, with the establishment of Real de Las Palmas near the Guiniguada ravine, and concluded with the surrender of Ansite in 1483.

Alonso Fernández de Lugo, who had participated in the conquest of Gran Canaria, was granted the authority to conquer La Palma and Tenerife. The invasion of La Palma unfolded between 1492 and 1493, culminating in the deceitful capture of the indigenous chief Tanausú. Tenerife, the final island to be conquered, witnessed the first Battle of Acentejo, where the Guanches emerged victorious. Subsequently, a protracted guerrilla war ensued, punctuated by pivotal Castilian triumphs in the Battle of Aguere and the second Battle of Acentejo. The conquest formally concluded with the Peace of Los Realejos in 1496, although pockets of indigenous resistance persisted in the mountainous regions, known as the "uprising Guanches."

Finally, on December 7, 1526, Emperor Charles and Queen Juana issued a Royal Decree creating an appellate court in the islands with its headquarters in Gran Canaria—previously, the Chancellery of Granada was considered competent—which eventually became the common hierarchical authority of all the Cabildos and exercised a genuine governing function over the archipelago, evident from 1556 until the appointment of the first Captain General of the islands in 1589.

Conquest of Gran Canaria (1478–1483)

The initial stage took place from June to December 1478. Led by Juan Rejón and Dean Bermúdez, the first expeditionary force arrived at La Isleta on June 24, 1478. They established Real de La Palmas near Barranco de Guiniguada, which is present-day Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Shortly after, the first battle occurred near Real, resulting in the defeat of the islanders and granting the Castilians control over the northeast corner of the island.

From the end of 1478 until 1481, the period was marked by Guanche resistance and internal divisions among the Castilian forces. The indigenous population put up a fierce fight in the mountainous interior, while the invaders faced challenges such as limited resources and conflicts within their own ranks. Juan Rejón was dismissed by the Catholic Monarchs and replaced by Pedro Fernández de Algaba, who was later executed under the order of the deposed Rejón. The appointment of Pedro de Vera as the new governor and the arrest of Juan Rejón brought an end to the internal strife by 1481.

The final stage, from 1481 to 1483, involved the suppression of Guanche resistance and the complete conquest of the island. Pedro de Vera, now the undisputed commander, resumed the campaign, aided by reinforcements from Gomero sent by Diego García de Herrera. The Battle of Arucas resulted in the death of the Guanche leader Doramas. The capture of Tenesor Semidán, the king of Gáldar, by Alonso Fernández de Lugo played a decisive role in the victory of the invaders. Tenesor Semidán was sent to Castile, baptized as Fernando Guanarteme, and after signing the Calatayud Pact with Fernando the Catholic, he became a loyal ally of the Castilians.

After the end of the indigenous resistance in the interior of the island in 1481 and the capture of Tenesor Semidán, the guanarteme of Gáldar, by the Castilian Adelantado Alonso Fernández de Lugo, the signing of the treaty known as the Carta de Calatayud took place. The treaty was signed between Tenesor, representing the Kingdom of the Canaries, and Ferdinand the Catholic, King of Aragon, on behalf of the Kingdoms of the Spains. This treaty made the Canary Islands part of the Crown of Castile, and Spanish military commanders stationed in the Canaries were granted land, as were the different guanartemes, menceyes, or tribal kings, who remained as political authorities.

With the fall of Gáldar, the indigenous resistance against the treaty with Spain shifted to the mountainous areas of the interior. There, Bentejuí, with the support of the faycán (shaman-advisor) of Telde and the princess of Gáldar, Guayarmina, organized the final resistance in the rocky heights of the island.

Tenesor met with them in an attempt to convince them to cease the rebellion. On April 29, 1483, he had a conversation with Guayarmina Semidán, who, like him, was a descendant of the Semidán, and with Bentejuí at the fortress of Ansite, steadfast in his defiance. After the meeting, Guayarmina came down and surrendered, while later on that same day Bentejuí and the faycán of Telde embraced the ancestral ritual of committing suicide by jumping off a cliff, proclaiming "Atis tirma" (For you, land). The precipice that bore witness of this sorrowful fate has been given the name of Atis Tirma, as a testament to their sacrifice and indomitable spirits.

With their death, all armed and organized resistance to the conquest of Gran Canaria by the Catholic Monarchs came to an end.

Conquest of La Palma (1492–1493)

Alonso Fernández de Lugo, a key figure in the conquest of Gran Canaria, was granted rights to conquer La Palma and Tenerife by the Catholic Monarchs. The agreement entailed a fifth of the captives and 700,000 maravedís as a reward if the conquest was completed within a year.

To finance the endeavor, Alonso Fernández de Lugo formed a partnership with Juanoto Berardi and Francisco de Riberol. Each partner contributed a third of the expenses and would receive an equal share of the benefits.

The campaign progressed relatively smoothly, beginning on September 29, 1492, with the landing in Tazacorte. Alonso Fernández de Lugo employed agreements and pacts with the Benahoarites, respecting the authority of the chieftains and granting them equal status with the Castilians, in order to win their support, and were transferred to Gran Canaria. Resistance was generally limited, except for an incident in Tigalate. However, in the canton of Aceró (Caldera de Taburiente), Chief Tanausú mounted a more organized resistance, utilizing the natural defenses of the terrain.

After two failed attempts to penetrate the Caldera, Alonso Fernández de Lugo realized that time was running out and he feared the loss of the bonus of 700,000 maravedís, so he sent Juan de La Palma, a relative of Tanausú and ally of the Castilians, as a messenger to convince Tanausú to surrender, converse to Christianity and submit to the Catholic Kings promising to bring them presents. Tanausú sent as answer to the Castilians that they retreat from the Aceró, and that they meet on the next day outside his territory. Lugo agreed, but feared Tanausú and his men would retreat towards the rough grounds of the Caldera or ambush them. He awaited Tanausú and his men at the place that was agreed upon and then attacked the Benahoarites. After a bloody battle, the aboriginals were defeated and Tanausú was captured. Tanausú was taken away to be presented to Ferdinand and Isabella. In defiance, Tanausú is said to have refused to eat during the journey to Spain, and died without seeing land again. Fernández de Lugo proposed a meeting with Tanausú in Los Llanos de Aridane. The Castilians ambushed and captured Tanausú as he left the Caldera. He was subsequently transported to Castile as a prisoner, but tragically perished from starvation during the journey. The official end date of the conquest is recorded as May 3, 1493. Following this, a portion of the population in Aceró and other cantons that had signed peace treaties were sold into slavery, although the majority were integrated into the newly formed society after the conquest.

Conquest of Tenerife (1494–1496)

Tenerife was the final island to be conquered, and it took the longest time for the Castilian troops to subdue it. The traditional dates of the conquest span from 1494 to 1496, but attempts to annex Tenerife to the Crown of Castile began as early as 1464. Thus, 32 years passed from the first attempt until the island's ultimate conquest.

In 1464, Diego Garcia de Herrera, Lord of the Canary Islands, symbolically took possession of Tenerife in the barranco del Bufadero. A peace treaty was signed with the menceyes (Guanches chiefs), allowing mencey Anaga to build a tower on his land. However, the tower was later destroyed by the Guanches around 1472.

In 1492, an unsuccessful raid organized by Francisco Maldonado, the governor of Gran Canaria, resulted in defeat for the Europeans at the hands of the Guanches of Anaga.

In December 1493, Alonso Fernández de Lugo obtained confirmation from the Catholic Monarchs for his right to conquer Tenerife. In return for renouncing the bonus promised for the conquest of La Palma, he claimed the governorship of Tenerife, though he would not receive revenue from the quinto real tax.

The conquest was financed through the sale of Fernández de Lugo's sugar plantations in the valley of Agaete, acquired after the conquest of Gran Canaria, and by forming an association with Italian merchants settled in Seville.

At the time of the conquest, Tenerife was divided into nine Menceyatos (kingdoms) that can be categorized into two factions: one largely in favor of the Castilians, known as "el bando de paz," and the other opposed to them, known as "el bando de guerra." The bando de paz consisted of the peoples in the south and east of the island, who had prior contact with the Castilians through missionary activities. The bando de guerra, based in the northern menceyatos, fiercely resisted the invasion.

In April 1494, the invading force, consisting of Castilian and Canary Islands soldiers, landed in present-day Santa Cruz de Tenerife. They constructed a fortress and advanced into the interior of the island. Negotiations with Bencomo, the most important king in the bando de guerra, failed, leading to inevitable conflict.

The First Battle of Acentejo took place in a ravine called Barranco de Acentejo, resulting in a significant defeat for the Castilians, with the loss of eighty percent of their forces. Fernández de Lugo managed to escape to Gran Canaria, regrouping with better-trained troops and more financial resources.

After receiving aid and supplies from Inés Peraza, a neighboring territorial lord, Fernández de Lugo returned to Tenerife. He rebuilt the fortress at Añazo and defeated Bencomo in the Battle of Aguere in November. The use of cavalry and reinforcements led to the Castilian victory. The Guanches lost many men, including Bencomo. The impact of an epidemic on the outcome of the battle remains disputed.

In December 1495, the Castilians, after a period of guerrilla warfare and war fatigue, advanced towards Taoro from the north. The Second Battle of Acentejo resulted in the collapse of aboriginal resistance and opened access to the Taoro Valley, marking the conquest of Tenerife and the end of the Canary Islands' conquest.

The conquest of Tenerife concluded on July 25, 1496, with the Treaty of Los Realejos between the Taoro mencey and Alonso Fernández de Lugo. In celebration of the peace agreement, the first Christian church, Parroquia Matriz del Apóstol Santiago, was built in the Orotava Valley, honoring the patron saint of Spain.

Role in the conquest of America

The conquest of the Canary Islands played a pivotal role in the subsequent discovery and conquest of America by Castile. The Canary Islands served as a strategic base for Castilian sailors and explorers venturing into the Atlantic. They provided a stopover point for resupplying ships, repairing vessels, and recruiting new crew members. Additionally, the knowledge gained from the conquest and colonization of the Canary Islands, including navigation techniques, shipbuilding expertise, and contact with indigenous peoples, proved invaluable during the expeditions to the New World.

Paul Chapman argues that Christopher Columbus drew insights from the Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis, particularly regarding the favorable currents and winds for westbound travel via a southern route from the Canary Islands. Likewise, he utilized a more northerly route on the return journey, capitalizing on the same principles. As a result, Columbus followed this itinerary on all of his voyages.

Sources

(Coming soon.)